Elena Comay del Junco

PERSUASION

Yeah like that that’s perfect, right over there yes no a little higher. Yeah come on, right there just like that keep going, no a little more. Yes yeah don’t, I mean no don’t, stop keep going. No—like that. Just like that yes no, that’s right you got it don’t worry it’s good. Yeah that’s perfect no, go back yeah, to what you were doing yes. No yes keep going, I don’t want you to stop. Don’t stop. It’s never too much, stop never stop. Stop—stop, no,

What I want is I want you to keep going, not to stop, to not stop, to keep going, even when I tell you to stop—no I don’t want to come up with and/or agree on a word that isn’t “stop” but tells you to stop, which is to say a word that means stop but isn’t “stop”—what I want is I just want you to not stop, I mean what I want is for you not to stop but—

What I don’t want is I don’t want to tell you not to stop so that when you don’t stop it’s not that you didn’t stop after I’d told you to stop. No, it’s just that I want you to not want to stop—that is, in other words, what I want is for you to want to keep going, to want not to stop, not to want to stop, for you to stop yourself from stopping.

What I also want is to not stop wanting you not to stop—in other words I want to stop you from stopping, but I don’t want to stop you from stopping by telling you to stop, to which you then respond by doing the opposite of what I tell you, which is to say by not stopping. That’s no good.

No, what I want is I don’t want you to leave, but I do want you to want to leave but to stay because I want you to stay. I mean I still want you to want to stay but I want you to do it because I want you to or, in other words, for you to want to stay because I want you to stay. Or actually maybe—

What I want is I want you to stay because you want to stay, which is the same as for me to want you to stay because you want to stay rather than for you to stay because I want you to stay. One of us, though, has to not want you to stay for this to work, since we can’t both want you to stay without the other, right?

It (a) doesn’t make sense plus (b) doesn’t sound like much fun. Or?

Here’s another way of putting it, which is that I wouldn’t ask you to do anything unless I knew that you wanted me to ask you to do it, or, in other words, unless I knew that, even if you hadn’t thought of me asking, I knew that you would want to do it without me asking in the event that, without me asking, you somehow thought of it—

Another way of putting all of which is: that I wouldn’t want to ask you if there was any question about what the answer would be, which still counts as a real question, not a rhetorical one (which is just a sentence in the form of question to make a point)—this one still needs to be a question because otherwise nothing would happen, I mean not if I didn’t ask.

Another thing I want is that—if I were going to add anything—I would want you to immediately want to do “it,” whatever “it” is, without my having to ask, even though my asking was and/or is and/or will be a prompt for you to do it, but ultimately is accidental. What I mean is that if someone else suggested it (I mean, suggested that you do it to me) or if it just popped into your head—yeah, just like that—you’d have the same reaction.

What I mean is that I’m definitely, 100 percent, absolutely not saying that what I want is for you to do anything that you wouldn’t want to do without my asking, that is to say something that you only want to do because I ask you to even if, after I ask you, you really do want to do it—

See, what I don’t want is, I don’t want to detect even an iota of self-sacrifice, not a drop, or, if there’s to be self-sacrifice, I want it to be my self-sacrifice, however selfish that may be, but anyway—

What I know is that this probably sounds a little bit like I’m trying to get you to be at my beck or at my call, this is to say that I want you to do whatever I ask you to do because you want to do whatever it is I ask. It might sound like that’s what I’m saying but that would be wrong because that line about “your wish is my command” has always seemed backward—

(And no, it doesn’t have to do with the fact that it’s a catchphrase associated with Oriental despotism most widely known, at present at least, because of its inclusion in a Disney movie that I haven’t seen, based on a likely-spurious addition to the Thousand and One Nights by a Frenchman in the early 1700s who was supposed to have had very good Greek Arabic Persian Turkish Syriac Latin Italian etc. god I’m getting jealous)—what I mean is just that I always thought it should be that your command is my wish, right?

Which yes, I do know could just mean that you’re so bent around my finger (is that the phrase?) that you don’t just want what I want but want whatever I say you should want whether or not I actually want it. But, in fact, I should clarify that it’s not that I want you to wish for it because I command it but that I only want to command it if, in fact, you wish for it, which makes it not a command, except that it has the shape of a command, when you’re looking in at the sentence from the outside—

Which is all to say that I’m trying to give you what you want by telling you what I want you to do. Or, in other words, I only want something from you if you already want it first.

What it’s not is—it doesn’t have anything to do with gender, please. Recall PG, that

Il faut voir dans ce désarroi d’alors, un des termes de cette volonté pulsionelle contradictoire d’être à la fois vu et voyeur (voyant), mac et pute, acheteur et acheté, baiseur et baisé.

See, nothing to see there, right?

The problem is really just that, after all, that “your command is my wish” is the same thing as “your wish is my command,”

which is the same thing as:

“My command is your wish” and “my wish is your command”

which is just the same as:

“Your wish is my wish” and “your command is my command” and “my wish is your wish” and “my command is your command” and “your command is your wish” and “your wish is your command” and “your wish is your wish” and “your command is your command” and “my wish is my command” and “my command is my wish” and “my wish is my wish.”

And so, regardless of the conclusion at which we arrive as we move forward, it is VERY important not to become the same person. Avoid the first-person plural at all costs. CC: All. High Priority.

***

What she meant when she said that “I consider it a defect that I don’t want a toilet brush up my ass,” was that, for many years, she found it difficult, indeed impossible, to watch footage of fisting. This lasted until she attended a screening of a film in which the protagonist switches from a hand to a toilet brush going in and out of their ass. With regard to being unaffected by images of fisting, an ability which anyone would be quite reasonable in supposing worthwhile to possess for any number of reasons, this sequence of images had a salutary effect. This was especially true given that her own inability was accompanied by an unease whose source lay, above all, in a feeling of inadequacy concerning her own capacitiesThe strategy she adopted in effecting this transformation, albeit without intention or even awareness of having done so, was a classic negotiating technique: raising the initial demand past the aimed for outcome with the hope that the settlement one arrives at—which has now been positioned as a compromise position—is in fact the original goal. In order to successfully employ this stratagem, one should, of course, be open to the possibility of this maximal opening demand being met—i.e. that this asked for outcome, however improbable or unlikely its realization might be, is a desirable one.In the above case, her husband understood the object to be some sort of implement with metallic bristles, a barbecue scraper perhaps, or simply a mass of steel wool attached to the end of a stick—an implement which, needless to say, is of a quite different sort than a standard toilet brush, with bristles of plastic or perhaps, for the more environmentally conscious consumer, some sort of natural material, such as jute.On discovering her husband’s misunderstanding, she realized the gravity of her situation. It would be one thing if she had come to be inured to moving images both of fists and of the standard sort of toilet brushes used as a prop in the film. Metal, though, was quite another.The first question, then, has to do with what the imagined possibility of this other, metallic, object as penetrative agent does to the status of the toilet brush—that is, whether it has the same, or at least a similar, effect for the brush as the brush did for the fist.There is also a second question, more difficult to formulate, yet perhaps also more critical. A friend who witnessed this exchange, which took place on the uptown D train, remarked that it the husband’s mistake seemed to him to constitute valuable material for the development of what he termed the “theory of the husband.” While this remark was, of course, made half-jokingly, it nevertheless posed a question whose answer we shall have to pursue in due course.The following morning, still tired after a long night of conversation—if not to say full blown negotiation—followed by a quite difficult time getting to sleep, she found the apartment empty and a note on the kitchen counter, reproduced in full below:

Do you imagine metal bristles or toilet brush? A theory of the husband by Elena Comay del Junco, book writer

Is this fun? I don’t know I, am having a hard time of it yet. But I am determined to have a good time. Even if my wife makes fun of me. I suppose this must be part of the theory (of the husband, who imagines the metal bristle going up the butt of the guy [sic] in the movie, as opposed to a toilet brush, which helps the viewer, here a future wife, watch fisting without fear.Last night we talked about pressing flowers and also about fisting. Today, I am sitting next to a tulip and what do I see? I see a fist. I must be a husband. The flesh of a tulip is too tender to be pressed or go up an ass. In trying to develop this theory properly is it required to perform experiments or just to do some simple guess work? My wife has recently been saying that she wants to “collaborate” with me. What does she mean? Is she asking to metal bristle me? I can only hope! Or me her? Time to go to the hardware store.

***

So, what I want is I want you to be persuaded—I mean persuaded to give it to me whatever it is. We’ll have to come back to that later but for now once again what I need is I need you to use your imagination—or what I’d really like is for you to be of the persuasion, I mean already persuaded, no need for an argument, forget Jane Austen, please.

What I don’t, let me be clear, want is to convince you, to do any persuading, to put up a fight, to persuade you, to have to use wiles, feminine or otherwise, to talk you into it; what I want is just that I want you to be convinced, to have some conviction—not to listen to me attentively, to take it all in. No really, it’s not about you weighing my words, not a matter of giving me your undivided attention—

Anyway, don’t ignore me, absolutely not, no—

What you shouldn’t want is you shouldn’t be waiting eagerly for me to persuade you to wear you down, to keep asking until you agree to it to make such a good argument that you’re convinced that you’re all in that there are no doubts left at all—

No, you should already want it, be totally persuaded but without thinking about it, such that if someone (a step-sister, or -uncle, say, or step-teacher, -wife, -neighbor, etc. etc.) were to walk up to you on the street in the bar in the train in your bed in the kitchen etc. etc. saying:

“Are you, you know…”

And you say, “No, what.”

And this step-neighbor or whoever says, “You know—of the, you know, persuasion?”

You say, “Oh ya, of course.”

Clearly what you should want is you should want to do what I want—I mean, insofar as we’re working within this hypothesis, you should want it since that’s what I want—without my asking you, really without being asked at all, no need for it, no commands no vocalization at all—

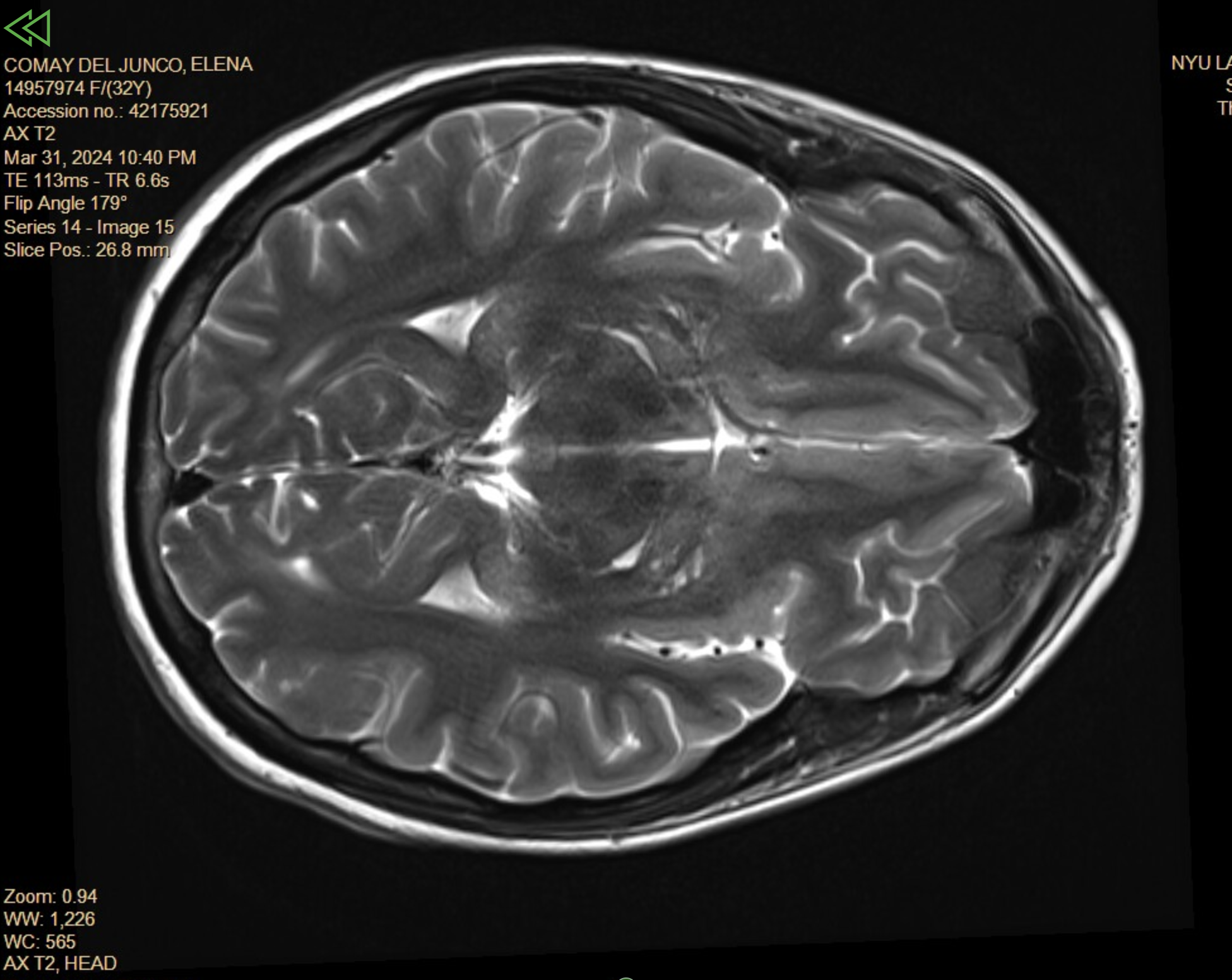

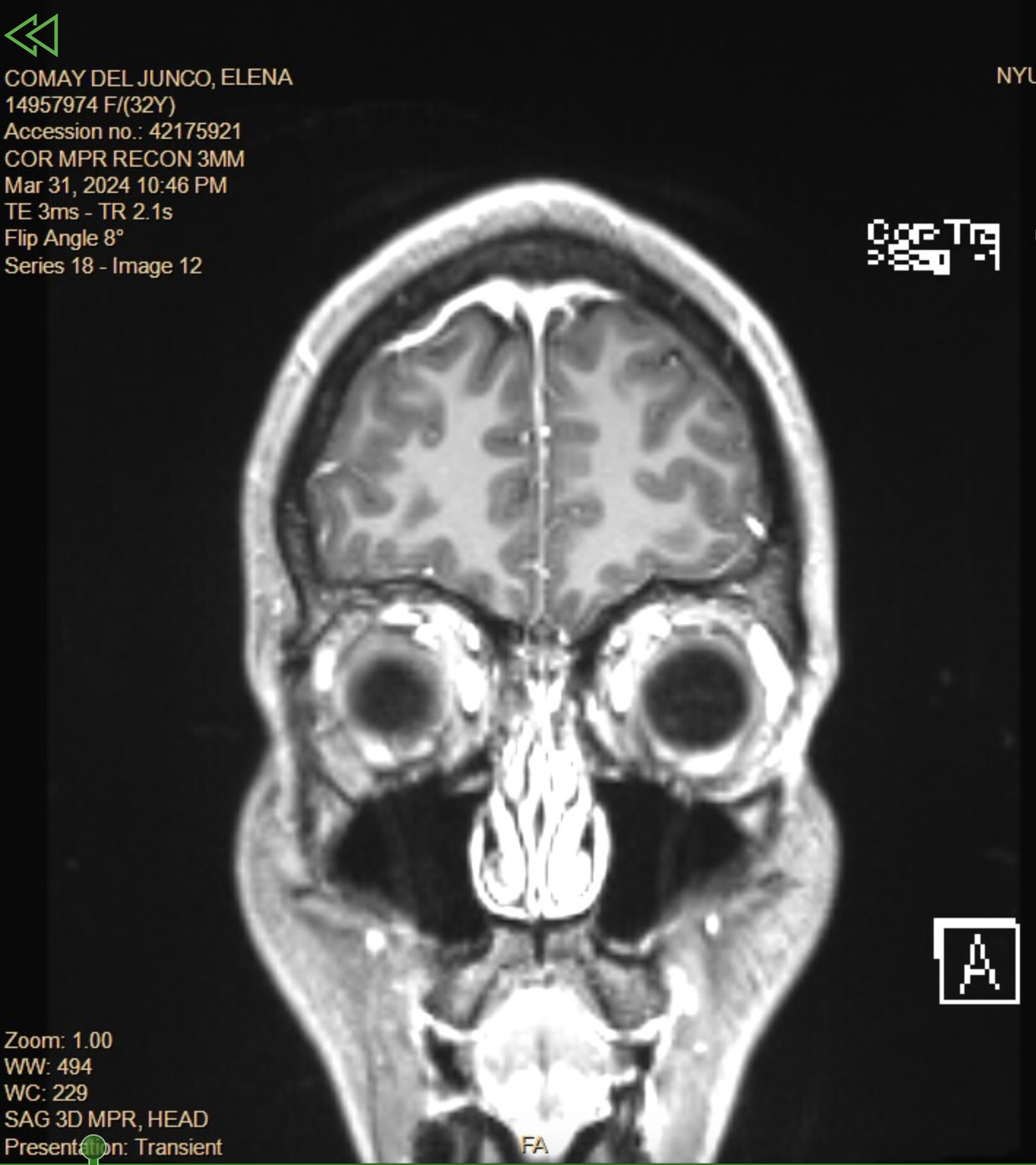

Just look right into my brain—where I want you to look is to look right here. Look, I got this MRI just for you. Look at it, I’m showing it to you, it’s full of goop, stick it in if you think it will feel good, I bet it will; everyone loves finding something new and squishy soft warm wet tight etc. why is this different? What, you’re too afraid to make your own hole, it has to be pre-cut?

Another way of saying this, which might seem to be the kind of thing that you—and here I mean you, in the proper second person, non-metaphorical sense—may well hate, which is to say that maybe something’s gone missing, what we need is we need to start again maybe, perhaps it’s not such a good idea to keep going, we need to stop—

What I mean is I don’t want you to be upset, I mean it doesn’t matter that we can’t keep going since you know you don’t need to persuade me, I’m here I’m persuaded, I’m of the persuasion, I’m not going anywhere not even moving an inch, right here, fixed in place, displaying the stable fixed disposition that you like so much, the one you prefer to anything else, whether it amounts to anything or not—

Let it be said again that it’s not a sex thing, not this time, not in the sense that that’s limited, or limiting, or too narrowly delimited a way of imposing limits or, if you prefer, it’s a sex thing even when it doesn’t look like one,

(This is also why, by the way, sadism and masochism only look different from the outside, which is also to say that, when it comes down to it, in their core they amount to something entirely distinct from their more familiar, outward appearance, which does of course look like a mésalliance.)

In other words, what I want is for you to just keep saying to yourself—without the sarcasm with which this phrase is often used—that “IT’S THE THOUGHT THAT COUNTS.”

Elena Comay del Junco is a writer and philosophy professor. She lives in New York and her recent work includes a chapbook "Second Nature" (mo(o)on/IO, 2023) and a translation of Ibn Sina's commentary on Aristotle's Metaphysics Λ (2024). www.ecdelj.com